Welcome to the Yubaverse

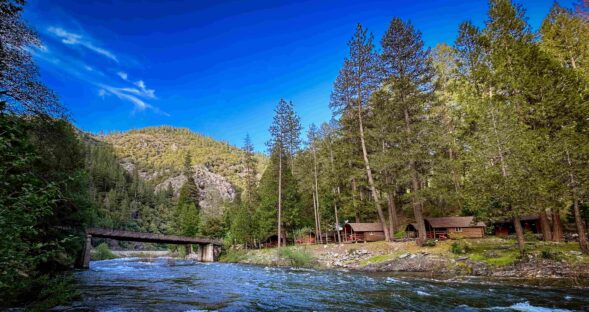

Escape to the Yubaverse, your gateway to outdoor adventures, community fun, and endless relaxation. Whether you're a seasoned hiker, biker, climber, river otter or a casual nature enthusiast, the Yubaverse is the perfect place to reconnect with the great outdoors.

Stay

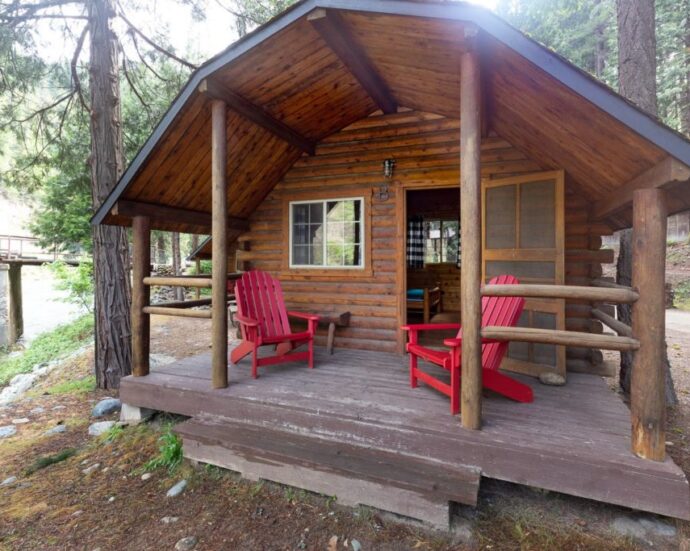

Stay cozy and close to nature with two cabin options set along the banks of the Yuba River — the perfect base to retreat to after a day outdoors.

Play

Whether it’s hiking, mountain biking, fishing, four-wheeling, rock climbing, or kayaking; On the water, mountains, roads, or trails — the Yubaverse is the perfect launch pad for your next adventure.

Gather

Gather in the great outdoors. The Yubaverse is a space for community and connection, offering a serene backdrop to your next gathering. Bring people together for weddings, retreats, events, & more.

Explore

There’s Gold Rush-era mining towns and ghost towns waiting to be explored and some of the most scenic rivers, pristine lakes, and breathtaking mountain views in the state. The Yubaverse is perfectly situated to immerse yourself in the natural playground of the Lost Sierra.

Plan Your Stay

The Yubaverse offers two ways to stay: eight full amenity cabins and six river huts. Our full amenity cabins offer modern accommodations for a comfortable stay: hot showers, clean sheets, & morning coffee with a view. Our camping huts are a great option for those who want simpler, no-frills accommodations along the river and include a shared bathroom and shower area. Bring your sleeping bag and headlamp!

Get Outside & Explore

Splash into refreshing emerald waters. The Yuba River offers excellent spots for summer swimming with deep pools and plenty of rocks to sunbathe. Sections of the Yuba River also offer Class IV to Class V rafting for adventurous water sports enthusiasts.

Explore More

Over 20 small lakes, 30+ miles of world-class hiking trails, picturesque waterfalls, high mountain views, and historic lodges. Get exploring with a wealth of outdoor activities for adventurers of all kinds – even the four-legged!

Explore More

The majestic Sierra Buttes beckon adventurers to come and explore their rugged beauty. These soaring peaks offer some of the most awe-inspiring views in the region and plenty of hiking trails and climbing for everyone. Check out the Sierra Buttes Fire Lookout trail for 360-degree views of the Buttes — a top 10 hike!

Explore More

A little gold rush town in the heart of the Lost Sierra — Downieville is a hidden gem that offers visitors a unique taste of the rich history of the American West. Take a stroll through downtown with its beautifully preserved 19th-century architecture, historic buildings, and quaint shops in one of California's most scenic and historic regions.

Explore More

Your Launch Pad for Adventure in the Lost Sierra

A destination for sharing good times together outdoors.